Demography is dead.

Demand is fragmenting. The conventions around categories are being abandoned. Marketing to the masses, or even the majority, is no longer enough to guarantee success. Consumers are demanding ever greater personalization, while at the same time their needs and preferences are growing increasingly diverse. No matter the product, selling to this fragmented market requires a whole new approach.

Personalized pricing presents an ideal solution to feed shoppers’ need for both individuality and value—without forcing retailers and brands to sacrifice margin.

As it exists today, personalized pricing is the process of customizing offers and promotions to individual consumers based on their past purchase behavior, price sensitivity and propensity to buy. (Though commonly used interchangeably, personalized pricing is not the same as dynamic pricing. Dynamic pricing is actually pricing that changes in response to factors unrelated to the consumer, such as weather, time of day and market demand.)

Personalized pricing has been around for several years—particularly online. But thanks to the growth of consumer data and advanced analytics platform, it’s getting a lot more attention across all channels, including brick-and-mortar. Shoppers’ redefinition of value and their increasing desire for customization is also playing a role.

According to proprietary research from Daymon, the majority of global shoppers—six out of 10—have an interest in greater engagement with retailers, brands and the shopping experience as a whole. These engaged shoppers define value beyond price and seek out differentiated retail experiences that are tailored to their needs, attitudes and lifestyle. Personalized pricing can deliver on this desire—and at the same time, helps retailers end their participation in the race to offer the lowest price.

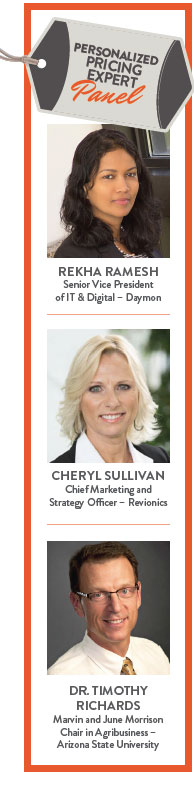

“Personalized deals make shoppers more likely to spend more overall,” says Dr. Timothy Richards, economist and chair of agribusiness at the Morrison School of Agribusiness at Arizona State University. But perhaps more importantly, he explains, they also allow retailers to get more value out of each transaction. “Shoppers will pay more for some items and less for others, but on net—the retailer will be able to make more money.”

“Shoppers are price-sensitive, but not on every item,” agrees Cheryl Sullivan, Chief Marketing and Strategy Officer for Revionics, a leading profit optimization software company. Rather than simply chasing competitor’s prices or having promotions for promotions’ sake, “it’s really about understanding what your shoppers’ key value items are and being competitive on those items.”

OK, so you get that personalized pricing and promotions are a good thing. But how exactly does it work—especially in the brick-and-mortar space?

OK, so you get that personalized pricing and promotions are a good thing. But how exactly does it work—especially in the brick-and-mortar space?

“You have to be able to segment shoppers more granularly—for example, separating cat buyers versus dog buyers,” says Sullivan. “You also have to know where best to reach the customer, what the ultimate right price is and then what kind of offer they’re going to respond best to, whether it’s buy-one-get-one, or a coupon or a flat percentage off.”

Sullivan admits this is a pain point for many retailers. “A lot of retailers just repeat the same promotions over and over again and accept different results. Most don’t have a lot of promotional data… [so they] don’t really have a good idea of what their promotions are actually doing for them. We’ve found that out of 90 percent of promotions, revenue comes from only 30 percent, and 85 percent of the profit comes from the top 15 percent [of promotions].”

Taking the time to collect and analyze existing pricing and promotional data is a critical first step. Advanced software and machine-learning technologies can then help predict future promotions that will be the most successful. Add in consumer data and those promotions can be targeted down to the personal level.

One caveat, says Rekha Ramesh, Senior Vice President of IT and Digital for Daymon, is that the consumer data used can’t cross the line into discrimination. “Personalized pricing can be a fine line when it comes to legality,” she explains. “As long as you’re basing it on consumer behavior, like past purchases or Google searches, and not demographics, like race or ethnicity, it’s considered more acceptable. A good example is using past purchase data to cross sell or incentivize certain behaviors, which is expected by the consumer.”

Once you know the right pricing and promotions to offer, delivery is the next issue. Unlike mass promotions, you can’t advertise personalized deals in a circular or even on the shelf. Fortunately, the widespread use of digital technologies presents an ideal alternative.

Grocery retailer Safeway’s “Just 4 U” program is a good example. By linking their loyalty card to the retailer’s app or a profile on the retailer’s website, shoppers can browse and download personalized price offers and digital coupons for redemption in the store. The personalized offers are based on previous purchase habits, helping to ensure their relevancy.

By requiring shoppers to take action in order to receive these personalized prices and deals, a model like Safeway’s helps avoid what Dr. Richards says is one of the key challenges of personalized pricing: consumer perceptions of unfairness. “I was involved in a personalized pricing study where the premise was that a consumer would walk through the store and use their smartphone to get personalized prices sent to them. It sounds good in theory, but we found people don’t like getting a worse deal than other people,” he explains. “If they think that other people might be getting a better deal, they won’t come back.”

By requiring shoppers to take action in order to receive these personalized prices and deals, a model like Safeway’s helps avoid what Dr. Richards says is one of the key challenges of personalized pricing: consumer perceptions of unfairness. “I was involved in a personalized pricing study where the premise was that a consumer would walk through the store and use their smartphone to get personalized prices sent to them. It sounds good in theory, but we found people don’t like getting a worse deal than other people,” he explains. “If they think that other people might be getting a better deal, they won’t come back.”

Dr. Richards research also found, however, that this perception of unfairness can be mitigated if shoppers’ have the opportunity to participate in the price formation process somehow.

“Smart couponing is one way to get there. If shoppers are spending their time to get the lower price, others are more likely to accept it as fair that they pay more if they don’t put in that same effort,” he says.

Another innovative strategy a retailer in Europe is trying is crowdsourced pricing. Carrefour, one of the largest hypermarket chains in the world, introduced a campaign in France in late 2016 that allowed its shoppers to vote on the price of a new line of milk that was being introduced. Shoppers were asked to choose how much they thought farmers should receive per liter, with different amounts affecting the final retail price of the milk.

Overwhelmingly shoppers chose a higher amount (39 cents per liter) than what was considered the world standard (27 cents per liter). This amount was described as an option that would allow farmers to earn a living and pay for a replacement when taking time off. The final retail price of 99 cents per liter, which shoppers also approved, was 10-30 cents higher than the typical price for unbranded milk.

While not fully one-to-one personalized pricing, this crowdsourcing model provides a similar level of perceived customization and fairness by allowing shoppers to participate in the pricing process. It also proves that many shoppers are not simply focused on getting the lowest price (only three percent voted for that option in the milk survey). They’re willing to pay more—allowing more margin for producers and retailers—for items that take their needs and preferences into account and align with their values.

Combining personalized pricing with customizable products and services is yet another avenue for retailers to explore. “Personalized pricing becomes even more acceptable and compelling if the product is also customized. This way shoppers can’t compare their pricing to others because the end product is not the same,” says Ramesh. She points to opportunities to expand this personalization proposition across many industries—whether it’s offering customized salad mixes at grocery, tailored garments in fashion, or build-your-own specs in computers.

Ramesh says the practice of personalized pricing will continue to rise, and retailers would do best to begin sooner rather than later. “Developing a personalized pricing and promotion program isn’t just about having the data or the technology. It needs to be integrated across multiple different systems and departments,” she explains. “You have to align your Marketing data, your POS data and your social media data, for example.”

Sullivan is also bullish on personalized pricing and believes retailers can overcome the challenges. “We know that getting there can be big and daunting, but you can do it in stages. You have to do it or you’re going to get left behind. If you are not looking at new technologies and ways to reinvent yourself and aligning against who the shopper is today, you’re just not going to be in business.”

Sullivan is also bullish on personalized pricing and believes retailers can overcome the challenges. “We know that getting there can be big and daunting, but you can do it in stages. You have to do it or you’re going to get left behind. If you are not looking at new technologies and ways to reinvent yourself and aligning against who the shopper is today, you’re just not going to be in business.”